Measure Your Wellness

CGMs have been around for a long time, but they were typically used by diabetics in order to measure blood glucose, balance their diet, and know when to administer insulin.

Because You Can't Fix What You Don't Know

Last week, I stabbed myself in the arm.

That's a tad dramatic.

But I did attach a Continuous Glucose Meter (CGM) onto of my arm, which includes a small metal filament the size of a "kitten's whisker" -- those are not my words, they are directly from the manufacturer's materials -- in order to take blood glucose readings every 5 minutes.

There was also a needle in the applicator device that is used to insert the filament. I will just say that needle looked a lot bigger than a kitten's whisker to me. Nevertheless, I did it!

For the past week I've been able to monitor my blood sugar in near-real-time, and I feel like I have glucose superpowers.

CGMs have been around for a long time, but they were typically used by diabetics in order to measure blood glucose, balance their diet, and know when to administer insulin. These days, the devices have been gaining in popularity outside of this limited audience, specifically within the biohacking movement.

What is Biohacking?

If you're not familiar with biohacking, it's any behavior that takes a scientific understanding of your body into account to enhance results. These results can be literally anything that you would want to improve of maintain about your health.

- Want to lose weight? There's a hack for that! Balance your blood sugar with a diet low in carbs. Measure your blood sugar or ketones with a CGM or breath meter. Exercise near meals (before or after) to lower blood sugar spikes, and cut out highly processed foods that hijack your brain chemistry to make you crave more. Even counting your macros is a form of biohacking, using the molecular composition of your food to understand how it will impact your physiology.

- Want to sleep better? There's a hack for that! Monitor your sleep with wearables, don't eat within a few hours of going to bed. Reduce your blue light exposure in the evening, and make sure to see sunlight soon after waking. Make sure that when you get in bed, you are trying to get to sleep, not lying in bed on your phone! What did I just say about blue light?

- Want to avoid jet lag? There's a hack for that! Fast for at least 16 hours before "breakfast" time in your new time zone. This probably means forgoing the airplane food. Honestly, you're better off for it. Also avoid caffeine during this time. Then break your fast at morning time in your new timezone in order to reset your circadian rhythm. You may still feel tired -- after all, plane sleep is basically trash -- but in my experience, this process avoids the vision-swimming tiredness that comes from a sudden inversion of night and day during international travel.

I won't go into too much detail here, but watch for this topic in another article! Biohacking also includes fasting, light therapy, manipulation of heat or cold, sleep tracking, HIIT training, and selective diets, as well as biomarker tracking such as blood testing, CGMs, and even smart watches that measure any bodily metrics.

My Biohacking Journey

I've been steadily increasing the amount of biohacking in my life for years, though I didn't always call it that. As a naturally curious and analytical person, it just makes sense to me that you would test different strategies and measure the results to the best of your abilities.

Exercise Intensity

I dabbled with the idea of the "7-Minute Workout" while I as in graduate school. I barely had time to sleep, let alone work out, but I wanted to do some kind of activity for my health. This tightly packed circuit training cycle claimed to give the same benefits of 45 minutes at the gym thanks to the varied and intense exercise and rapid transitions.

Later, I learned that this technique is somewhat similar to the strategy promoted by Dave Asprey -- the father of modern biohacking. The strategy he promotes in, Smarter, Not Harder, is to exercise as intensely as possible for very short periods of time, then bring your heart rate back to baseline as quickly as you can.

The workout is based on the idea that we are simulating the mad dash to escape from a predator. The initial intensity signals our body that we need to improve and our life depends on it. Returning to a calm state tells the body that we have successfully escaped, and its safe to switch back to "building" mode, rather than the "burning" mode used to run away. With this contrast, Asprey claims we can rapidly build muscle to prepare ourselves for next time, rather than continuing to deplete our energy stores in fight-or-flight mode.

FitBit

At one of my jobs, I was able to select a fitness-related prize once per year through the employee benefits program. In the three years I was there, I chose a FitBit Blaze, a Withings smart scale, and a NutriBullet Blender.

I won't discuss the blender, since it's not really a biohacking tool. Although, I have used it to make quite a few Keto-friendly salad dressings!

The FitBit, an early brand of fitness-focused smartwatch, tracked steps, heart rate, resting heart rate, and automatically recognized and recorded exercise sessions. At the time, I thought it was incredibly high tech. Little did I know that soon we would be able to track so much more.

I did eventually get a Samsung Active Watch to replace this one, which was more advanced, but largely the same in terms of health metrics.

Withings Smart Scale

The smart scale was another cool addition to the fitness tracking family. It measured weight (duh); heart rate, which was a little redundant next to the watch; and body composition, which was the cool new thing at the time. By sending a small electrical charge up through one foot and out the other, the scale could measure the resistance of your body and could somehow calculate -- or at least approximate -- your bodily makeup of fat, muscle, bone, and water.

I say "approximate" because I'm relatively certain that the amount of bone in my body hasn't changed over the years, but according to the scale it's gone both up and down about 0.2 lbs here and there. I find that unlikely, but overall the body composition metrics were interesting and informative.

Polyphasic Sleep

Another venture of biohacking that I explored was my crusade against sleep. I've often been frustrated by the pure wastefulness of spending a third of our lives asleep. How much more could we do, live, and experience, if that wasn't the case?

For quite a while, I was intrigued by the concept of polyphasic sleep, which basically means intentionally sleeping in any schedule other than the typical one solid chunk per night. In most cases, that also means reducing the total number of hours slept by making your sleep more efficient. The most intense Polyphasic sleep schedule, Uberman, involves sleeping for six quick 30-minute naps, for a total of only 3 hours per day.

When I experimented with this, I was totaling 4.5 hours of sleep broken into three segments. It was an extremely productive time, but it was also much more important to make sure that my sleep quality was sustained.

Smart watches claim to track sleep quality, but the data they have to do so is limited. Instead, I sought out a device specifically for tracking sleep.

Zeo EEG Headband

I purchased a device that was legendary in the polyphasic sleep forums: the Zeo. The device was a silly-looking headband with a single-channel EEG, the same kind of technology used in sleep labs. The device could be worn while sleeping to track the electrical activity of your brain and get the most accurate picture of REM, Deep, and Light sleep phases.

The Zeo provided the first true evidence that what I had read about Polyphasic sleep was true. My body was adapting to fall very quickly into Deep sleep during the longer of my three sleep sessions, and the other two were 70% or more REM sleep. I was fascinated by the results and by the idea that I could use technology in order to measure and optimize my own body, essentially hacking my physiology.

Eight Sleep

More recently, I purchased an Eight Sleep mattress cover after hearing about the product on both the Huberman Lab and DarkHorse podcasts. The mattress cover heats or cools the bed by running water through a network of tubing. It adjusts the bed's temperature during the night to optimize for different stages of sleep.

This is my favorite biohacking technology by far. At least, it was until the glucose meter. Now, it has some competition.

The Eight Sleep has far more accurate sleep measurements than any smart watch I've used, including your breath rate, heart rate, movement, and body temperature into it's calculation of sleep quality. The app is well designed, and the heating and cooling features work amazingly in both the cold of winter and the heat of summer.

I love crawling into a pre-warmed bed, and believe that I fall asleep much faster when I don't have to wait for my feet to warm up.

Evolving Technology

Though these are the main technologies that come to mind from my personal biohacking journey, I've experimented with dozens of other strategies that don't require any tools of the trade.

From daily sunlight exposure, to saunas, to diets including Keto, AIP, and intermittent fasting, I've tried many things already and plan to keep on trying. New strategies are constantly emerging, and technology makes gathering real metrics for your personal biology a little easier every year.

With all the available wearables, software tools for interpretation, and science around supplementation, there is now an endless range of possibilities for testing, understanding, and improving.

Why I Took the CGM Leap

While I am loving the CGM, I have to admit it's one biohacking tool that might not be for everyone.

They tend to be expensive, for one thing. Many services charge $200 or more per month to use them, though if you go through a traditional doctor, insurance might cover it. Mine will cost between $143 and $184 per month if I use it continuously. Currently, I signed up for a 6-month plan at the lower rate.

I may cycle on and off of using it to try to practice the dietary patterns I learn without the immediate feedback. I don't plan to be using this thing for the rest of my life, after all.

For another thing, they are one of the more invasive forms of biohacking, since it requires direct contact with your blood in order to function. There are plenty of biohacking techniques -- like timing your sleep or meals, exercising in certain patterns, or measuring biometrics with other smart devices -- that are a little less, uh... vampiric.

That said, it's not as invasive as a blood draw, and likely less uncomfortable than a daily cold plunge!

So, why did I end up going for it?

Guesswork Isn't Enough For Health Metrics

We can easily be doing everything we "should do" and still be making mistakes. Ignorance of a problem does not mean there is no problem.

People ate margarine in the 90s, oblivious to the dangers of trans fats and believing it was the heart-healthy option compared to butter. Millions of people continue to make the same mistakes with so-called heart-healthy cereals, granola bars, protein shakes, and energy drinks. And don't get me started on processed and fast foods.

We can look and feel healthy, while having a lurking medical condition. It's possible, even likely, that the condition will wait to reveal itself only after it's progressed beyond the point of a simple fix. Everyone knows that "catching it early" is one of the best defenses for most of the worst potential ailments. It gives the chance to start treatment before it has the chance to progress.

So what information can we trust? We have misinformed doctors operating on decades old information. Government guidelines gave us the food pyramid, years ago, and are slow to change as new information comes out, if they acknowledge the new information at all. Silent health conditions and chronic disease are ever more common in our society.

The only way to really know that we are healthy is to test.

Food Impacts Vary Dramatically Person to Person

What spikes my blood sugar, might not spike yours. There are some principles that appear to hold true for the majority of people, but you'll make a lot more impact on your personal health if you know specifically what works for you.

Some principles suggested by Jesse Inchauspé, in her bookGlucose Revolution, include:

- Eat food in the right order - Start with fiber first, then protein and fat, then finally carbs and sweets, or skip the sweets altogether.

- Add a green starter, such as a salad or a side of roasted or sautéed non-starchy vegetables

- Stop focusing on calories - Calories from quality proteins and fats will impact your metabolism much differently than will the same number of calories from sugar or carbs.

- Flatten your breakfast curve - Eat a savory breakfast, such as eggs and bacon with avocado, If you must include fruit in the morning, opt for low glycemic choices like green apple, unripe banana, or berries.

- When using sugar, use any type you like - They all contain fructose and sucrose and will impact your blood sugar in a similar way, but keep them limited.

- Pick dessert over a sweet snack - When you have to eat something sweet, do so following a meal instead of an empty stomach.

- Reach for vinegar before you eat - Mix 1 Tablespoon of vinegar in a glass of water 10-20 minutes before meals, especially if you plan to add something sweet or high-carb.

- After you eat, move within 30 minutes - Walking is the easiest way to implement this, but if you have active hobbies or go to the gym, just time those visits strategically!

- If you have a snack, go savory - Try carrots and hummus, hard-boiled egg, or some cheese

- Avoid "naked" carbs - Add butter to popcorn, cream cheese or a slice of turkey to bagel.

Besides these glucose "hacks" as Inchauspé calls them, she also makes a point to outline an experiment she tried with a friend of similar health and build to herself. The two women ate the same glucose-spiking meal, even some ice cream, then sat on the couch together. Inchauspé's blood sugar spiked hard. Her friend's was elevated, but not nearly as much.

This indicates that the same meal can impact different people in different ways. Perhaps this could be attributed to unknown health or metabolic conditions, but isn't that exactly the reason to test?

I've Seen it Working in My Own Family

My dad, who is in his mid-sixties, has been using a CGM on and off since some health problems two years ago. At the time, he was going through a lot of exploratory tests to find out what was wrong. His doctor suggested that he may be diabetic, but was definitely at least pre-diabetic, based on the blood test readings.

However, my dad is a rather scientific guy. He understood that some of the medications he had recently taken for the health problems, such as steroids and antibiotics, can raise blood sugar levels. While he believed his readings were high in that one sample, he wasn't convinced that he was chronically diabetic.

He convinced his doctor to prescribe a CGM so that he could monitor his continuous blood glucose.

Since then, he has been able to reduce the number of glucose spikes he suffers from to practically none. He has learned which foods are safe to eat, and in what quantities. He knows how to time a walk before or after dinner to burn off most of the immediate glucose from the meal.

At his last doctor's visit, the doctor declared all of his readings to be back in "normal" range.

Unfortunately, I don't believe that normal is good enough.

If a certain combination of biomarkers are all at the high ends of the spectrum -- even without crossing into "abnormal" -- that's not random. It tells a story. If LDL, Triglycerides, and fasting glucose are all up, but HDL is low, that indicates something is wrong -- likely something metabolic.

By getting my own glucose meter, I will be able to do experiments more quickly, share information with my parents, and learn more about my own health, diet, and metabolism. I can try out things I learned from Glucose Revolution, such as drinking a little vinegar water before a dessert, or lifting something heavy after a meal with moderate carbs.

What I've Learned So Far

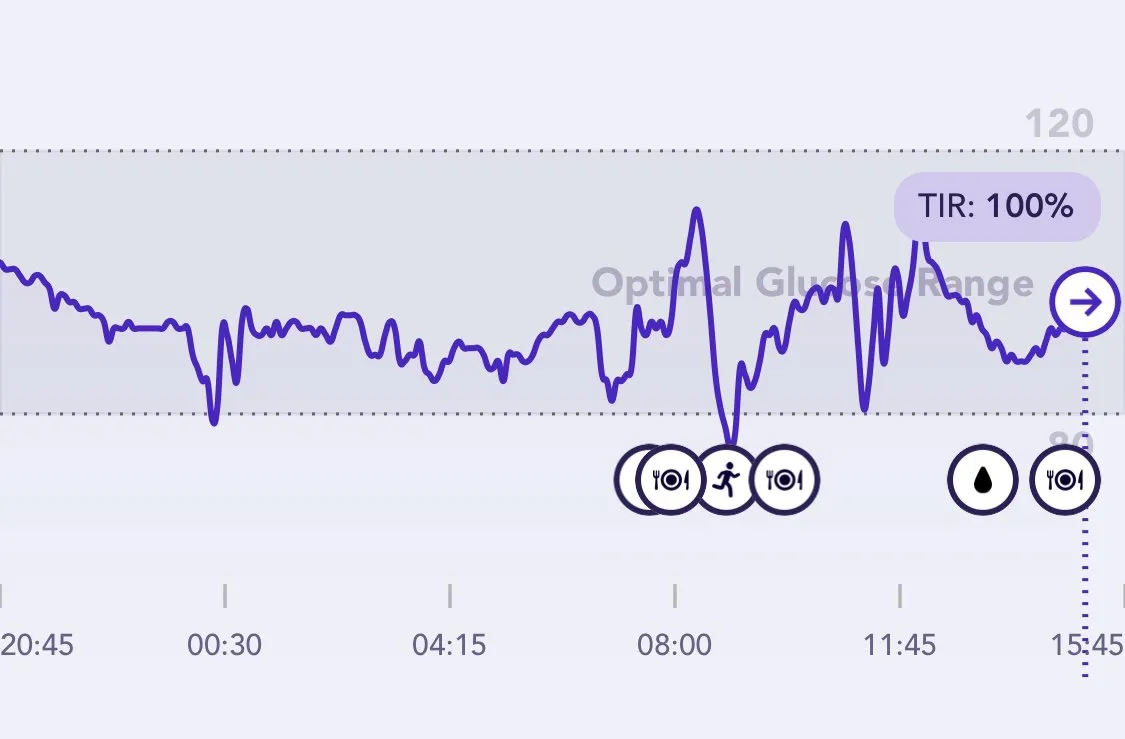

I'm only a week into my CGM journey at this point, but I'm pleased with my experience. I've been constantly refining my diet and routine and have learned how to stay in my optimal range for most of the day, and I've learned a lot, but still have a lot of experiments to do.

Step 1: Attaching the CGM

The first surprising thing about my CGM is that it really didn't hurt to place it. It comes with a plastic applicator about the size of my fist, which has a scary-looking needle inside that you can't possibly miss when taking off the plastic cap and getting ready to use it.

You press the applicator against the insertion zone, which for most people is the back of your upper arm, but I have also seen suggestions for the abdomen, thigh, or just above your butt if you have trouble getting accurate readings from your arm. You press a button on one side of the applicator and Click! the meter is attached instantaneously.

I felt the applicator click, and it made a surprising sound. However, I wasn't sure if I had actually attached the meter at first because it didn't hurt! I was pleasantly surprised when I looked over my shoulder and saw a little gray disk, flat against the back of my upper arm.

It took 30 minutes for the sensor to "warm up" before it was ready to start giving me readings, and my first day of glucose readings was wild!

Step 2: The First Meal

I've always been good at tests, and I believed I would pass this one with flying colors due to my typically healthy lifestyle. I was shocked when my first tracked meal of chicken curry with kale and a carefully measured 50g of rice sent me almost immediately out of my "Optimal Glucose Range," which was capped at 120 mg/dL. For reference, readings hitting above 200 mg/dL are cause for concern.

I didn't exercise at all this day, so that I could see what my readings looked like without physical activity to balance them. In hindsight, that was a terrible idea. It skewed my averages for the whole week, and left me concerned about both my overall average glucose level and the amount of time I was spending outside my target range.

Those concerns have dissipated over time, as I got a better handle on both my diet and exercise to manage my glucose. I rarely go outside of my 80-120 range.

Step 3: Experimentation

I've continued to experiment with different meal and exercise combinations, and for the most part it's what I expected.

- Simple carbs cause an increase, but less when paired with other macros.

- Exercising before or after a meal reduces the spike.

- Eating high fat and protein meals, such as an omelette or chicken salad with avocado and bacon, barely impacts my glucose at all.

One thing that did surprise me is how much fruit spikes my blood sugar.

In my experiments so far, the spike has been as much as +40 mg/dL, even for a small piece of fruit like one clementine of a handful of berries. I believe this was the case even if I ate the fruit at the end of a high-fat meal, though I didn't test that deliberately.

I learned that for me, it's better to workout or walk before a meal.

Exercising early sets my muscles up to absorb the blood sugar as soon as it hits. Doing so after a meal also has a positive effect, but it results in a funny horseshoe-like curve on my graph.

- My blood sugar will start to increase before the exercise increases my glucose burn

- It dips during the majority of the activity

- Then it continues to increase afterward, since digestion goes on for several hours after eating.

The routine of pairing exercise flattens the curve either way, but activity before produces a more smooth graph with a slower rise, rather than two small peaks.

I also learned that if I haven't eaten for a while and start to feel shaky, it's not in my head.

I felt this at one point while visiting a book store with my husband, and I checked my app to find that my blood sugar had dropped to 57 mg/dL. I've experienced this feeling a few times throughout my life, and I learned through that experience that it helps to eat something when it happens. However, much like the validation of successful polyphasic sleep, the validation that it was a real blood sugar crash and not a craving was very validating.

The last thing that piqued my interest, is that Omega-3s might have a protective effect against the spike from simple carbs.

I say this because my graphs for two similar meals -- one with chicken, and one with salmon -- were vastly different. I have a few theories, and I want to retest more deliberately, but either the high fat content in the salmon or specifically the EPA/DHA Omega-3s are currently my top suspicion, but I need more time to explore.

How to Try It Yourself

Luckily, It's no longer necessary to convince a doctor to prescribe a CGM in order to try it.

There are several services which I am aware of for acquiring a CGM 100% legally. They even come with custom mobile apps for monitoring and sharing your journey, if you happen to know others using the same service

I know there are a number of companies that offer CGMs these days -- Levels, Signos, Nutrisense, and Veri are the names I have seen.

I went with Signos here because they had good reviews, they use the latest model of one of the two brands of CGM I know of: the Dexcom G7, and the price was a little better than the other services at the time I checked it.

You can sign up for Signos using my referral code to save $250 off the 6-month plan, or $150 off the 3-month plan. The discount will show in the cart, not the pricing table.

Final Thoughts

Everyone has something to learn from health monitoring, whether through a CGM, regular blood testing, or biometrics sensors.

Given that a large number of Americans suffer from metabolic disfunction, testing for blood sugar and learning how to control yours is one of the best decisions you can make, and to me, the cost and inconvenience to do it once was worth it.

In the spirit of testing and measuring in order to identify problems and opportunities for improvement, I've also purchased an at-home blood test.

I haven't taken it yet, but I will soon and will devote another article to reviewing the results. There's a lot more valuable information in the blood than just what's found in the blood sugar, and this test will cover 17 metrics including a standard lipids panel, hormones, and cortisol. I plan to write about that test as well, so keep an eye out for it in the next few weeks!